In this site

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is the most effective non surgical treatment for cancer. It involves using high energy X-rays which damage DNA (the genetic make up) of cells. This can be sufficient to kill those cells, and because normal cells are less affected by radiotherapy overall (being better able to repair radiotherapy damage), relatively more damage is caused in cancerous cells. To maximize this effect, often a course of a number of treatments or fractions of radiotherapy are used.

The specific side effects and probability of controlling a particular tumour depends on the location, size and type of tumour as well as the sensitivity of the surrounding normal tissues/organs to radiotherapy.

Radiotherapy can be given to a patient by "shining" it in from the outside (external beam radiotherapy) or by an internal approach (brachytherapy).

External beam radiotherapy.

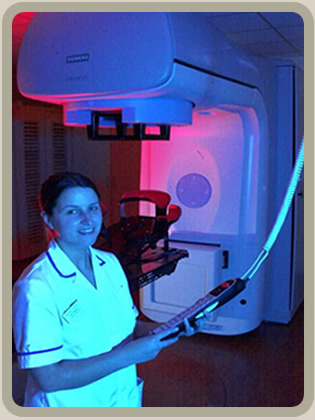

Radiation can be produced by a machine called a linear accelerator (see picture) and then focused at a target area within a patient. The patient will normally be lying down on a supported couch to receive the treatment, about one metre away from the machine. The treatment head of the linear accelerator can rotate around, and the patient couch can also rotate as well as move up and down. This means that the radiotherapy can be given from any angle. The treatment normally takes a few minutes and is very much like having a normal X-ray. The patient will not feel anything whilst the radiotherapy is being given. The patient will be alone in the treatment room whilst being treated, but can be seen at all times via a video link.

A linear accelerator (radiotherapy machine).

It is important to be as accurate as possible when treating with radiotherapy and some of the techniques that may be used for this include performing a CT scan to help target the treatment and making a plastic shell or using supports to keep part of the body still. Small, permanent tattoo dots for reference points on the patient may also be used and then lined up with lasers before each treatment.

A CT scanner, used to help plan radiotherapy accurately.

There have been many developments in external beam radiotherapy to improve it's accuracy and safety. The radiotherapy beam can be shaped (conformal radiotherapy) by using lead blocks or tungsten leaves built into the machine (called a multileaf collimator) and using several different angles of treatment to obtain greater concentration of radiotherapy dose at the target site. More radiotherapy fields can be used to even out the dose in the treated area, or to give different doses to different areas (intensity modulated radiotherapy or IMRT). As well as treating from a number of different angles, modern machines can give radiotherapy in a continual arc to enhance the dose concentrating effect, in volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT).To help in the accuracy of radiotherapy, scans can be performed just prior to treatment, making sure the target is covered and nearby sensitive normal tissues are not being hit by the treatment more than expected. Adjustments can be made to the treatment set up if there is variation in the target position before the radiotherapy is given. This is called image guided radiotherapy or IGRT. The linear accelerators at the Royal Cornwall Hospital have conformal, IMRT, VMAT and IGRT capability.

Brachytherapy

There are essentially two different techniques for internal radiotherapy or brachytherapy, namely intracavitary and interstitial brachytherapy.

Intracavitary brachytherapy can be used, for example, in gynaecological malignancies. It involves a special tube or applicator being inserted into the patient (in this case the vagina/womb), radioactive pellets being automatically introduced into the applicator, and then automatically removed once the required dose has been given. The applicator is then also removed. No radioactive sources are left inside the patient. The time this procedure takes depends on the dose required, and how quickly the radioactive pellets release radiation, but ranges from minutes to hours.

Interstitial (or into the tissue) brachytherapy means that the radioactive sources themselves are inserted into the patient. This can be done with radioactive needles or wire, which are subsequently removed, or by using radioactive seeds which stay in the patient forever. The latter can sometimes be used in certain prostate cancers.

Overall brachytherapy is used much less frequently than external beam radiotherapy. It is only potentially suitable for a limited number of patients and tumour types, location and stage.